[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]RAJASTHANI CITIES, JAISALMER AND BIKANER’S LANDSCAPE PRONOUNCE ITS ROYAL HISTORY. BUT WHAT DO YOU DO IF YOU WANT TO TAKE THE ROAD LESS TRAVELLED?

India’s largest state, Rajasthan, wears its history with pride and vigour. From the glorious Amer Fort of Jaipur to the regal Lake Palace of Udaipur, all remnants of history and culture are beautifully displayed for its guests.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

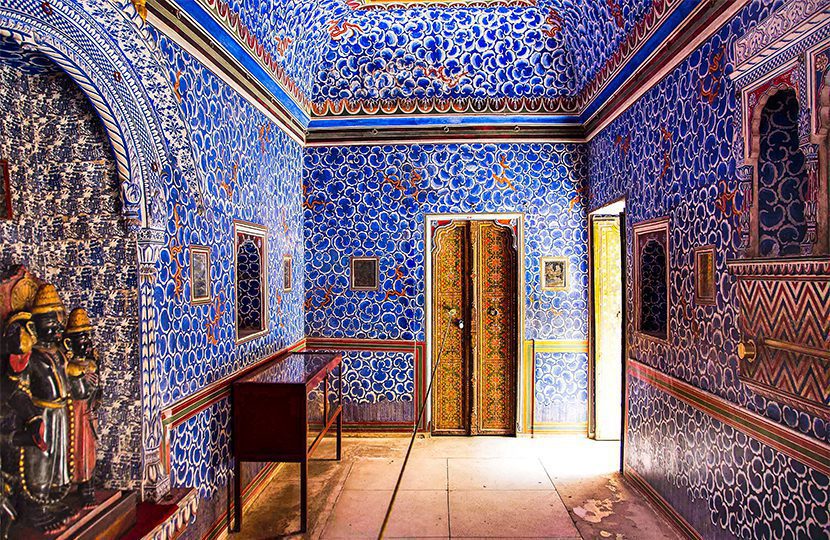

Peacocks are regular visitors at Suryagarh

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]But what do we expect to discover if we explore the lesser known wonders here?

Driven my curiosity, I prepared to explore Rajasthan with the help of a tailor-made experience that suited my spirit of enquiry. Suryagarh in Jaisalmer and Narendra Bhawan in Bikaner, took me across an experiential trail through the two cities’ history, architecture, economy and cultural practices.

Suryagarh as seen from the lake

SURYAGARH’S THAR EXPLORATION

The strong sun above Jaisalmer’s contoured dunes made it unpalatable to explore the bygone touch-points of the Silk Road. Passing through Chennai (then Madras) and Fatehpur Sikri, Rajasthan was perhaps one of the main states in this ancient trading route.

Nakul Hada, hotel manager of Suryagarh noticed my reluctance and said, “The Silk Route is only a short drive away now.” I endured the heat.

We drove pass Dedha village towards Khaba, about 30 kilometres away from Suryagarh. On my either sides I saw barren, flat deserts with stout deserted houses. Most of these dilapidated structures were a part of the famous Khaba village, now abandoned.

IN THE ENORMOUS DESERTED VILLAGE OF KHABA, THE GOLDEN, OPEN PAVILIONS OR CHHATRIS, STOOD OUT PROMINENTLY.

The Paliwal tribe, one of the first settlers of Khaba, were agriculturalists. They practiced the now obsolete concept of sati, the ritualistic immolation of widowed woman on the pyre of her deceased husband. The remnants of this belief system I saw spread over its landscape. Vertical slabs of carved figures jutted out from the otherwise uniform panorama. The carved figurines on these sati tombs depicted the wives who passed on alongside their husband (usually the larger figure).

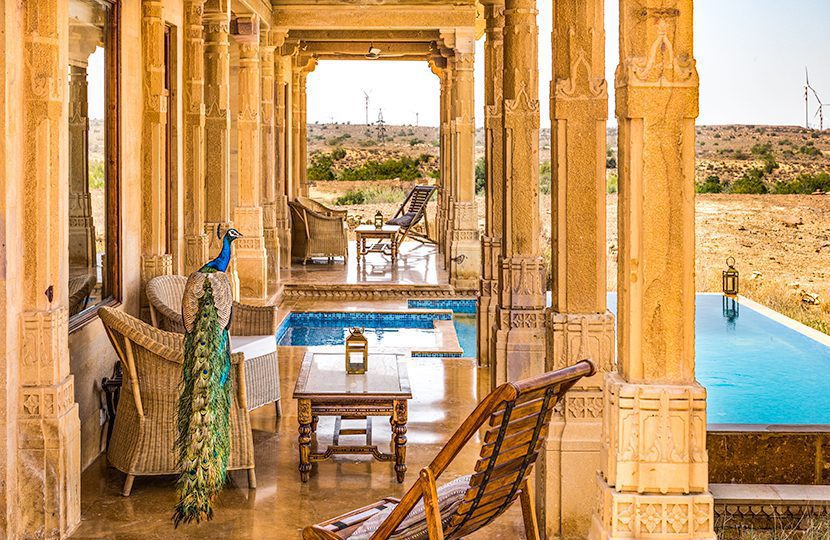

In the enormous deserted village, the most prominent structures were scattered across the panorama—golden, open pavilions. Also known as chhatris, these canopies were made by interlocking Jaisalmer’s yellow stone one with another. This 500-year old cantilever system also made the chhatris earthquake-resistant. These were now my faithful companions through my travel across Rajasthan.

An elaborate haveli lunch at Suryagarh

The following day I explored the touristy sandy mound of Bada Bagh. The uncharacteristic green grove of mangoes is frequented by many visitors. However, it was the cluster of chhatris where my interests vested.

The royal cenotaphs of Bada Bagh, encouraged by the sun, seemed to be rising in front of me. In various architectural styles—some bore the Mughal arches, some intricate Rajasthani latticed screens and others effortless symmetrical chhatris—each of the tombs stood gloriously against the blue sky. I climbed to the oldest cenotaphs, at the highest level, directly looking at the windmills. The engraved figurines and inscriptions adorned the tombstones. Some of these were carved on the native yellow stone while others on glistening white marble. Either way, all faced eastwards, towards the sun.

These cenotaphs date back to 1500s. Jaisalmer’s royal family were put to rest here and the oldest ones are at the top of the cluster. The figures and epitaphs resembled that of Khaba, though separated by minute distinctions.

Later in the day, Brahmsar sated my curiosity. Even though the chhatris of this temple complex, about 17 kilometres from Suryagarh, were not architecturally different from those I had seen, this place instilled calmness within me.

I SAW WINDMILLS BECOMING SILHOUETTES, GOLDEN SAND PARTICLES DRIFTING TOWARDS CITY LIGHTS. I KNEW THAT SURYAGARH’S THAR HAD CASTED A SPELL ON ME.

The temple complex of Brahmsar has been a pilgrimage site for Jains. It revealed itself in layers to me. The golden chhatris welcomed me and as I walked further inside, a neglected lowly-covered hallway led me to dilapidated rows of cenotaphs. The tombs were marked with faceless figures and covered with bird nests. However, the main temple was well-kept. An unassuming trail took me to the peaceful oasis. The winds glided on its still waters and passed through the chhatris—making silence audible. And much beyond I could see the golden sands of the desert.

Scrumptious platter at sundowner

On my last evening in Jaisalmer, Suryagarh manifested an extraordinary, handcrafted experience. A half-hour drive away from the grand hotel took me to the textured dunes of Desert National Park. A little before sunset, I sat studying forms and designs of nature as I sipped my golden glass of champagne. With the setting sun, Somar, the talented musician, played his double-flute, synchronised with the light breeze of the desert. At a distance, I saw windmills becoming silhouettes, golden sand particles drifting towards city lights. I knew that Suryagarh’s Thar had wound up its magic on me.

NARENDRA BHAWAN’S ROYAL LINEAGE

Rao Bika, founder of Bikaner, established his kingdom with the modest Bikaji ki Tekri. This fort was once the residence of royal families of Bikaner. It now commemorates the founding members with memorial stones of the families. The white marble or reddish-pink sandstone chhatris shade these stones.

From Bikaner’s first king to the last, Maharaja Narendra Singh, the residences of the royal descendants have changed many times. Each time, they have represented the king’s taste and style; the architecture mirrored contemporary trends and designs; and illustrated the prosperity of the state.

The sixth king, Raja Rai Singh, built the grand Chintamani Durg, or as we know it today, Junagadh Fort, when silk trade begun flourishing in Bikaner. In 1589, Chintamani Durg had become the new palatial home of the royal family and the succeeding 16 generations continued to live here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The fort-like Suryagarh blends in with the geography

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Under reign and governance of Maharaja Ganga Singh, this Rajasthani province witnessed major developments. After introducing the people of the city to three lifelines—electricity, water and steam engine— the 21st Maharaja capably administrated Bikaner.

Ganga Singh invited traders of Sujangarh to settle in Bikaner, who otherwise made short business visits and returned to their villages. The Maharaja allotted them land in the old city of Bikaner (now the neighbourhood of Joshiwara) to build houses and set up their trade. These traders hired local artisans to build their palatial homes and on the ground level, operated their shops.

A Maharaja’s tomb at Bada Bagh

One of the first settlers in this locale were the three Rampuria brothers, Bahadur Mal, Heera Lal and Hajari Mal Rampuria. The brothers owned seven mansions and the gorgeous Rampuria Chowk was named after the family. Like most other traders, they too traded goods on the Silk Road.

I stared at the magnificence of the Rampuria Havelis. From the ornate latticed balconies, lotus motifs on spandrels, to heavily patterned panels of doors—I noticed various elements of Indo-saracenic architecture. And the strong sun on Bikaner’s red sandstone brought the extraordinary relief work to life.

‘Rampuria Haveli was perhaps one of the first of the king’s subconscious effort to beautify Bikaner,’ I thought to myself at the first glimpses of the grand Laxmi Niwas Palace. Built by the same red Dulmera (a village about 65 kilometres away from Bikaner) sandstone, this palace exemplified the royal persona of the city.

FROM LARGE TRAVEL COLLECTIBLES TO CRYSTAL MINIATURES, NARENDRA BHAWAN HAS ALL ELEMENTS OF WHAT COMPRISES A REGAL MUSEUM.

Laxmi Niwas Palace was built between 1898 and 1902 by Maharaja Ganga Singh, after his royal residence, Lallgarh Palace, proved insufficient to host his grand parties. In Laxmi Niwas, the king welcomed and hosted royal dignitaries and military associates from all over the world. He made these associations when he was part of the Paris Peace Convention in 1919 and League of Nations in 1924, among the other international conventions. The guest list of Laxmi Niwas was the who’s-who of the times, with names such as Lord Curzon, King George V and Queen Mary gracing the residence.

Pushpendra Singh posing in front of Rampuria Haveli

And so it was no surprise that this palace had epitomised Rajasthan’s splendour. Vintage chandeliers hung from the high ceiling as I walked towards the open central courtyard. Cusped arches lined this courtyard and above, Rajasthani jharokas or enclosed balconies with diamond-shaped trelliswork added to its beauty. Flower motifs filled every dado, corner and edge. I admired the contrasting play of light-and-shade in the corridors while grasping the intricacies of antiques, artefacts and collectibles that paved my way.

The only resemblance that the 21st king’s Laxmi Niwas Palace bore to the last king’s Narendra Bhawan was the red stone facade. The intricate carving also made an appearance, though subtly.

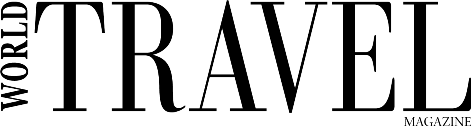

Narendra Bhawan was the residence of the last king of Bikaner, Maharaja Narendra Singh. The haveli turned hotel is based on a reflection of the king’s life. From the large travel collectibles to crystal miniatures, the hotel has been graced by various elements resonating his royal styles. I noticed the vintage cars at the entrance, the Italian marble marrying the Portuguese tiles on the floor of the porch, glazed Chinese vases on the edgy mirror table and robust Art Deco crystal tables in front of the leathered seats—all a part of the intriguing porch.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Dulmera sandstone of Junagarh Fort

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]As I took a step inside on the chequered hallway, a scarlet box imprinted with the Maharaja’s insignia, on the teal velvet bench caught my eye. A few steps away, I saw a pastel green coloured crystal chair reflect ambient light, creating diamond impressions on the ceiling. Though nothing compared to the grandness of the red piano, Edith, at the end of the hallway. The lyrics of Édith Piaf’s La Vie En Rose, painted in gold on the piano, only added to the harmony of the bold colours and patterns.

I was surrounded by these flamboyant design infusions during my stay at Narendra Bhawan. Soft shades of pink and green dominated my Prince Room (one of the four categories of rooms at Narendra Bhawan). These were further muted by the lacquered browns of the closet and the writing desks, which were complemented by the floral prints of lamps and patterned mosaic. And not once did this bold decor jar my eye.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Suryagarh overview

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]One evening, I sat at Gaushala, the open portico at Narendra Bhawan’s entrance, where guests enjoy cocktails and cool breeze of Bikaner. I titled my head to admire the dominant Indo-saracenic architecture of the hotel. As I lifted my cocktail glass from the orange layered onyx table, it occurred to me how Narendra Bhawan has contained the history of Bikaner, by smoothly blending in its bold royal persona.

Subscribe to the latest edition now by clicking here.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]